It wasn’t until this year that I finally got my hands on an HDR capable TV with real HDR content available to watch on it. And, I have to say that I was stunned by just how much better it looked compared to the SDR content I had been watching previously.

HDR is truly a huge leap forward, as much as the jump from SD video to HD video several years ago. And amazingly, it is already being delivered to homes and theaters across the country, with approximately 50 million HDR capable consumer displays sold in 2018. But for many reasons, this technology has not been truly embraced by productions and is rarely seen anywhere in the production pipeline outside of a colorist suite.

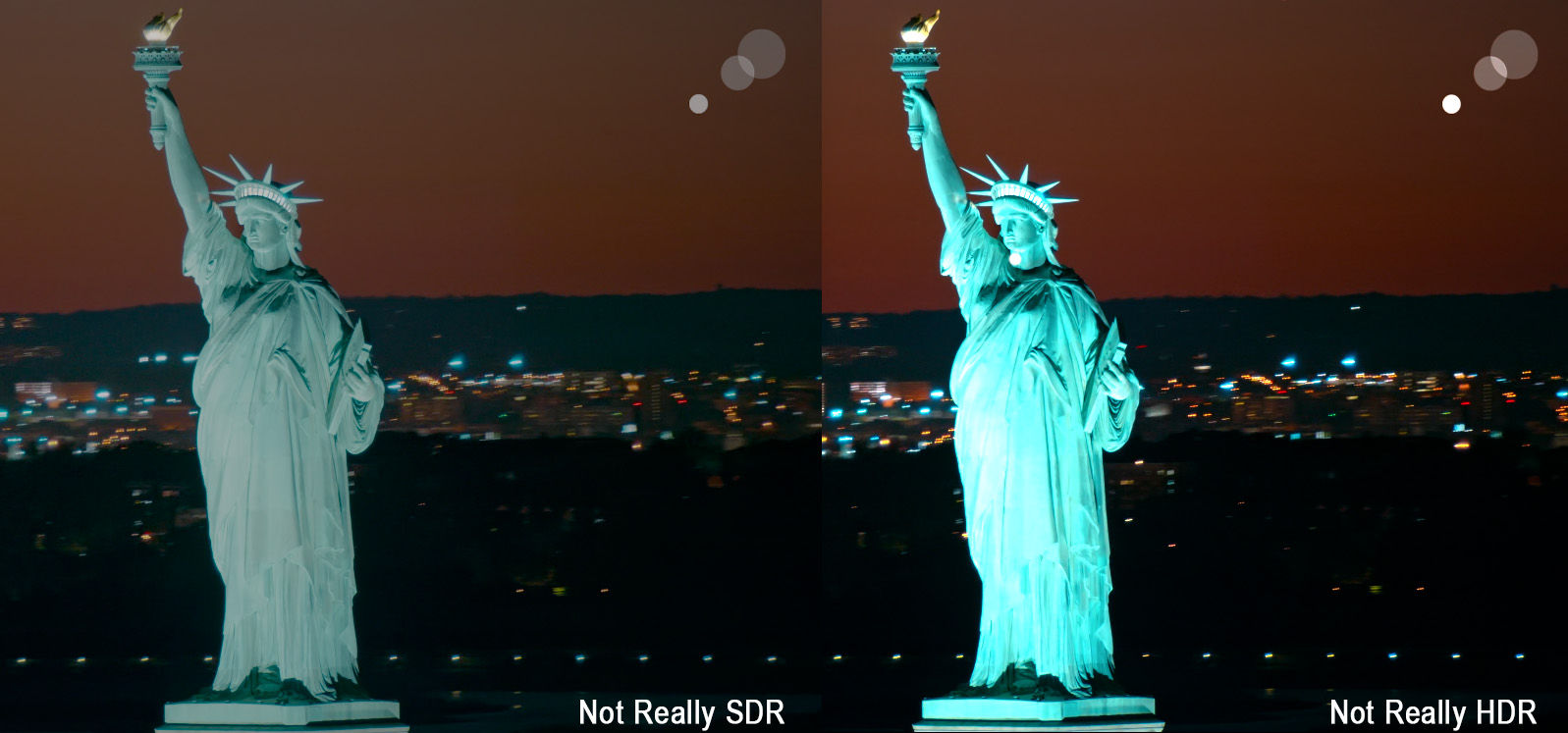

HDR is not something I can show you in this article. Sure I can add an image with a split screen of SDR vs HDR with one half looking washed out and the other half looking contrast-y and vibrant.

But that would not actually show you HDR because you are most likely not looking at an HDR screen at this moment. It is something you have to see with your own eyes to understand why it is important and not just another buzzword. This, in part, has slowed down the adoption of HDR in production, but there are other pinch points that are worth digging into as well. So let’s breakdown the challenges and talk about the technology available today.

Viewing HDR

Both Dolby and IMAX have created some amazing HDR cinema technology that is definitely worth experiencing in theaters, but perhaps the best place to get up close and personally understand what HDR is all about is right at home on a consumer HDR display. And the good news is that these sets have come down in price considerably (check out Dolby’s recommended list for the best of the best).

The display panels manufacturers have focused on developing are larger size (55” and up) HDR panels for consumers, as well as smaller displays for phones and tablets. That's right, many of you have an HDR capable display right in your pocket. If you have an iPhone X or newer, or the latest generation iPad Pro, check out the video below (just first crank up your phone or tablet brightness to max). Vimeo lets you enable HDR mode and the results are impressive.

HDR displays like this make economic sense for the consumer market, but have left a hole in the professional production market, where high-quality, medium-size displays (17–30”) are preferred. There are a handful of very high quality HDR finishing displays available, more on this later, but they come at a high price point or just aren't available yet. These factors have helped create a huge gap in the HDR pipeline of productions.

As streaming studios like Netflix and Amazon continue to increase the number of shows mastered and delivered in HDR, most productions today know ahead of time that HDR will be a required deliverable, and some considerations can be made in pre-production. However, at this stage of the game, the vast majority of HDR shows are not looking at HDR images until the finishing stage of production. Everyone working on set and in the earlier stages of production are essentially flying blind as to what their final image will actually look like.

This is not a new phenomenon; cinematographers shooting on film never expect to see a near finished result on set. For many years, there has been an expectation of seeing dailies and editorial looking roughly like the finished result. Yet this is not currently the case when it comes to HDR, where most everything is viewed in SDR until the finishing stage.

Lost in Translation

It is a common belief that looking at an SDR image on set and through editorial is “good enough”. But just like when we only had SD monitors on set for HD cameras, I would argue that you’ll end up missing a lot of small, but important details. There could be something unexpected in the shadows, such as a hidden stand or other on-set element. Or a bright area of the image that may overpower the overall scene, and unintentionally draw the viewer's eyes away from the main subject. From a cinematographers point of view, having an HDR monitor on set also allows them to better see their contrast ratios and may shape how they light a scene.

Beyond that, a less experienced cinematographer may not take full advantage of everything that is possible with HDR. They may not be aware of the full palette actually available, and so produce images that look rather flat in HDR. But perhaps the biggest problem comes with the familiarity of the SDR image over the HDR image. Over the many weeks and months of production and editorial, the SDR image is accepted by everyone involved, and it becomes harder and harder to deviate from that look.

Bridging the Gap

In an ideal world, every monitor used in production and through editorial would be HDR capable, and SDR would be an afterthought made only for in-flight entertainment screens. We will get there someday, but for now this is just not possible. So how do we bridge this gap in order to achieve the best possible results with the tools available today?

There are several HDR reference monitors now available that can be used for production, including the Flanders XM310K & XM311K, Sony X300 & HX310, Postium OBM-X310, TVLogic LUM-310R, and Canon DP-V2420 monitor. All of these will give you the widest possible color gamut, 1000 nit or higher output, and a very high contrast ratio (really black blacks). If you can get these monitors, even for a couple of days of testing, you will be in good shape. These monitors have built in transforms for handling the log input from most cameras, or you can use some additional color management hardware like the BoxIO or the AJA FS HDR, more on that down below. However at a $30,000+ price point each, they are not that practical for most productions.

The more affordable, but somewhat bulky option for viewing HDR on set is to use consumer panels. The LG C Series HDR OLED monitors, like the 55” C8 and C9 are great looking, output over 600 nit and have true black blacks. These, however, need to be combined with additional hardware, which converts SDI signals to HDMI and applies the right transforms for HDR viewing. My favorite combination is the AJA FS HDR with their Hi5 HDMI converter. This will allow you to view HDR on a big screen direct from camera. The AJA box is run by a special Colorfront Engine supporting a full ACES color managed workflow for both SDR and HDR, and it can even show SDR and HDR on the same screen. Flanders offers the XM551U and XM651U, 55” and 65” monitors, which have a similar feature set built right in, and at a similar combined price point.

For an even more economical option than the AJA box, you can consider the new Shogun 7 from Atomos. This is billed as an on-board monitor, but can also be used as a sort of HDR converter box to take in a Log camera signal and convert directly to HDMI in HDR. This essentially works as a plug-and-play option, but without the color adjustment options found in the AJA and Flanders solutions.

There are also 15” to 24” production monitors on the market today that claim to be HDR, and while these feature 600-1000+ nit outputs and HDR modes, they do not have the contrast levels needed to effectively view HDR. In actuality, pretty much any monitor with a traditional LCD backlight is not ideal for HDR in the field. At this moment, I cannot recommend any 15-24” production monitor, outside of the reference grade one mentioned above, for HDR on set. This may soon change, though, as Atomos has announced the new Neon series of HDR monitors in four different sizes, 17", 24", 31", and 55". These feature a high quality display that is very promising, and are built for production use. This is still new technology, though, and we are hoping to test these soon. Additionally, several computer displays have come out with support HDR modes, including the Apple Pro Display XDR and Asus ProArt PA32UCX & PQ22UC displays. These could all potentially be used for HDR in post production, as well as used in production use with the addition of the new Blackmagic Teranex Mini SDI to DisplayPort 8K HDR, which lets you convert an SDI signal right into a scaled signal for these displays via USB-C. Again, a lot of testing is needed to see if these solutions will work, but they are promising.

The Future Is Bright

Unfortunately, the HDR monitors built for production use are a bit limited at the moment, but the next generation of displays will start to show up in the next several months. Until then, it is important to understand what is possible with HDR. Take the time as an artist to learn how to take full advantage of the wider palette that has now become available to you.

It's also a good idea to experience HDR by viewing a proper HDR display and see for yourself what we are talking about. Watching actual content (not just a tradeshow reel) from Netflix, Amazon, or on Apple TV is eye opening. When you do, I think you’ll have the same revelatory moment that I did. Then you’ll be dragging an HDR monitor to set, and explaining to your significant other exactly why you need a new home television.

AbelCine encourages comments on our blog posts, as long as they are relevant and respectful in tone. To further professional dialog, we strongly encourage the use of real names. We reserve the right to remove any comments that violate our comment policy.

AbelCine publishes this blog as a free educational resource, and anyone may read the discussions posted here. However, if you want to join the conversation, please log in or register on our site.

We use Disqus to manage comments on this blog. If you already have a Disqus account registered under the same email as your AbelCine account, you will automatically be logged in when you sign in to our site. If not, please create a free account with Disqus using the same email as your AbelCine account.